- Date

- Image

- Text

- Title

- Size

- Medium

-

Christoph Steinmeyer – Haben oder Sein

22 April—30 May 2023

Michael Janssen, BerlinType “the most beautiful image in the world” into your browser and look for results. What picture do you expect to see?

In his ongoing artistic research project, spanning over eight years, German neo-surrealist Christoph Steinmeyer delves into the realm of popular imagery, probing the influence of algorithms, cookies and location tracking to uncover the mechanisms that shape our contemporary visual culture. This exploration has resulted in a series of paintings “The Most…”, into which the artist incorporates elements of internet culture and memes, using them to comment on the process of commodification of visual imagery.

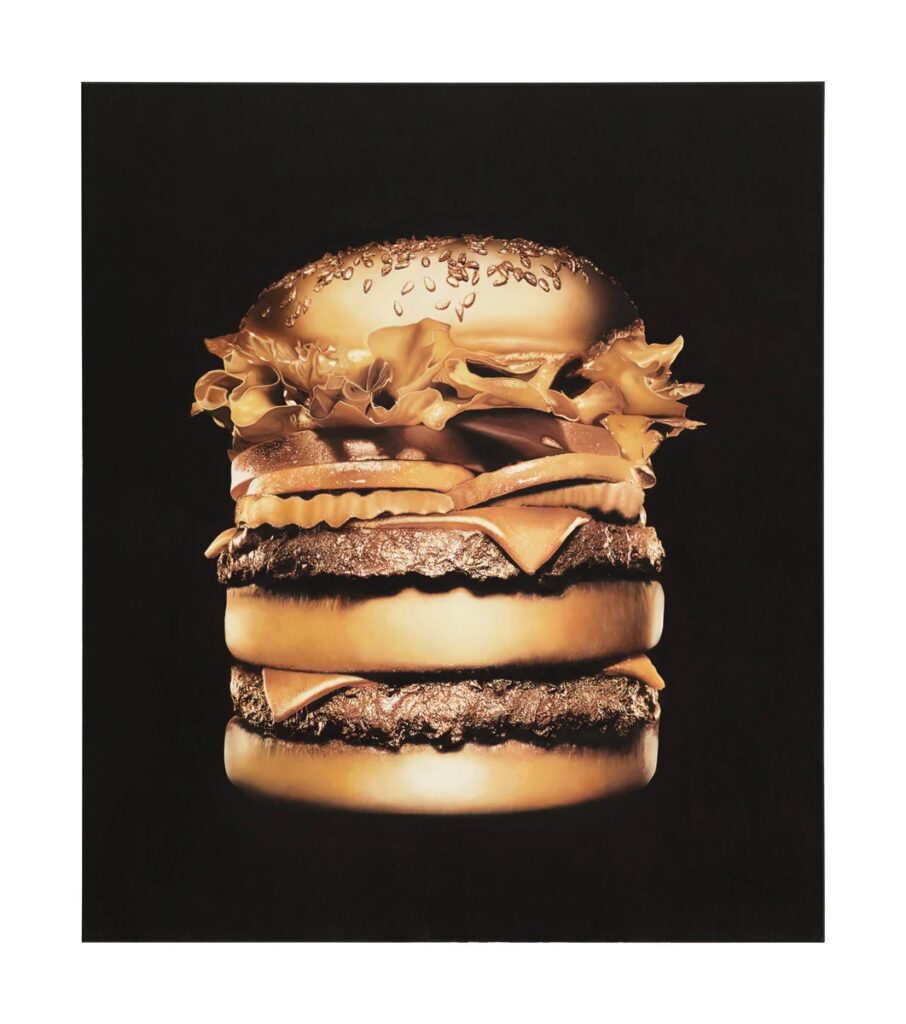

Steinmeyer’s interest in the ambiguous role of coveted contemporary artifacts is reflected in the title of his show, To Have or to Be? It references psychoanalyst Erich Fromm’s eponymous book which explores the fundamental differences between two modes of existence—having and being. In “The Most…”, Steinmeyer extends this debate by examining how, under capitalism, images are transformed into objects of desire that are filtered and artificialized to appeal to the masses. The series consists of hyperrealistic paintings depicting a golden hamburger, a tennis player—ephemeral glimpses into the search for absolute beauty on the internet.

Painted in seductive golden-yellow hues, the hamburger stands as a poignant symbol of consumer culture. The meat is depicted with photographic precision, evoking a sense of ravenous eroticism. Steinmeyer’s portrayal of the tennis player seems to draw inspiration from fashion photography that tends to objectify and sexualize public figures. However, the artist’s intention was to create an image of a modern Amazon, who uses her body as a powerful tool for feminist empowerment, rather than an object of male desire.

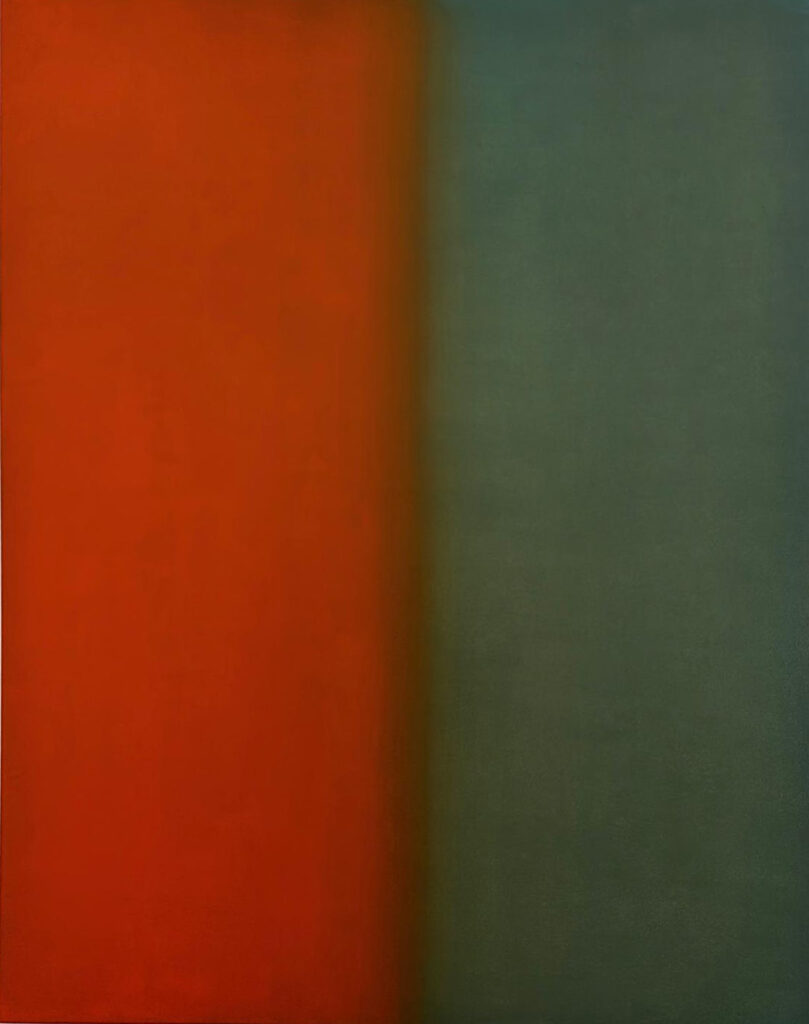

The “Most…” series employs a vivid chromatic palette characterized by contrasting colors that possess a tactile, almost velvety quality, reminiscent of lavish objects. The golden, red, white, and black hues have been meticulously chosen to enhance the exclusivity of the depicted images, eliciting a feeling of visual opulence commonly found in luxury advertisements. The use of such vibrant colors adds a layer of provocation and visual hunger to the paintings, inviting the viewer to indulge in pictorial consumerism.

In contrast to the confident palette of “the most beautiful” images, the introspective atmosphere of Steinmeyer’s landscape canvases is shaped by ambiguous grisaille tonalities that comprise multitudes of hues, granting the paintings a dream-like quality. We find similar gray-scale color compositions in the works depicting the launch of a rocket in desolate rural scenery. The empty wooden bench in the lower right corner, uncomfortably close to the canvas edge, intensifies the buzzing tension provoked by the sensation of absence —like a silent nightmare that unfolds in slow motion, electrifying the air with unsettling premonitions. The titles of the works, Challenge and Baltic Sea, hint at what this strange fantasy sequence might be about. The cinematically composed scene alludes to the tragic 1986 accident in which the American Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart, only 73 seconds into its flight. By transposing the spacecraft to the Baltic Sea, Steinmeyer creates a fantastic narrative that draws our attention to the real climate and humanitarian catastrophes present in Europe today.

Steinmeyer’s surrealism is profoundly conceptual. The meticulously repainted hyperrealist copies of his own works question the very essence of the debate about originality in art. How can we value a painting while knowing that it may be a reproduction?

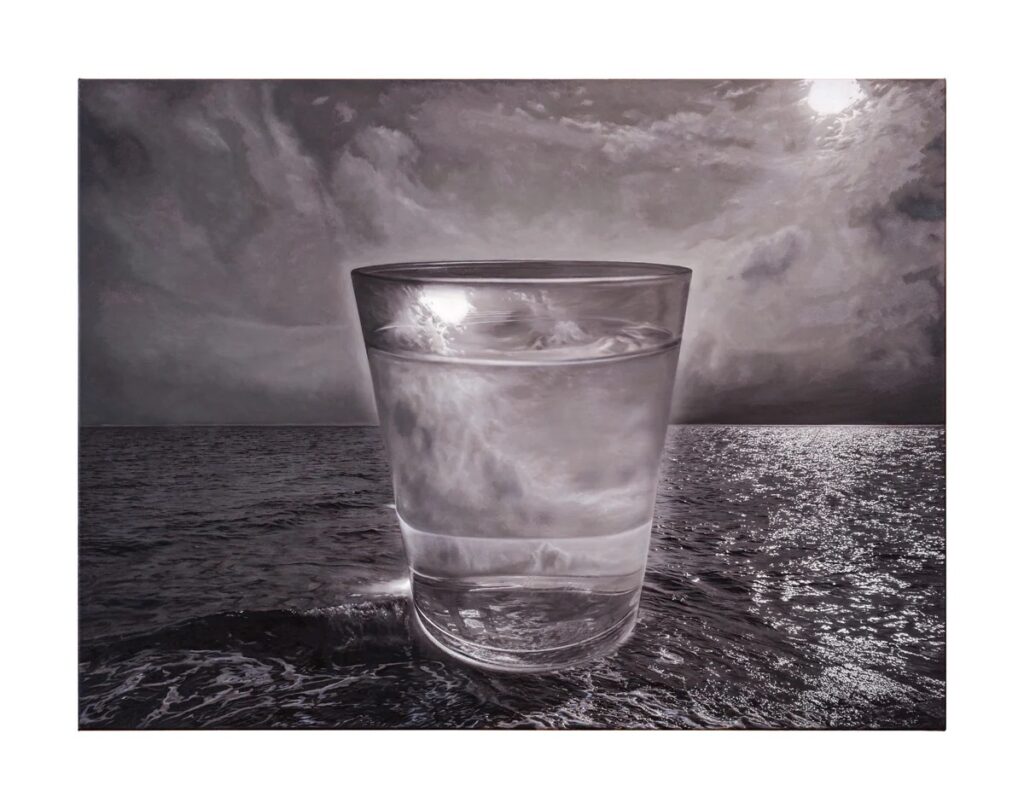

Challenge and Baltic Sea are identical replicas reproduced at different scales. When placed together, these duplicates mirror each other, trapping the viewer inside a labyrinth of multiplying reflections. Another vivid example of this poetic transgression is the artist’s series of four glass paintings, each of which playfully re-contextualizes the title of the show. The deeply personal transformative process the artist underwent during lockdown is portrayed through the tangled web of visual paradoxes that inhabit these oneiric seascapes, which Steinmeyer calls his self-portraits. Depicted in photorealistic detail, the sea shimmers under the faint sunlight on one side of the painting, while appearing devoid of light on the other side, as if the glass were blocking the sun’s rays from extending across the water. In contrast to the background, which remains almost unaltered in all four paintings, the sea inside the glass is presented to us in a variety of states: the serene translucency depicted in the painting “To Have and To Be” transforms into a dramatic tempest that distorts the limits of the image in “To Be or to Have”, providing a nauseating sense of motion as it bursts through the crystal. The physical installation of these paintings, hung in a linear row, endows the space in between with a tactile physicality palpable for the spectator. The absurdist logic of Steinmeyer’s surreal dreamscapes transgresses the limits of fiction, challenging the viewer with their amped-up intensity.

These introspective hybrids merge classical genres of landscape and still life painting into an existential chaos of magical hyperrealism where neither having nor being is relevant. Luminous portals into the threshold of becoming, Steinmeyer’s paintings project a high-resolution hyper-objectivity combined with an eerie panorama of oneiric distortions. Is it we who contain the sea? Or is it the sea that contains us?

Text: Karina Abdusalamova

-

Christoph Steinmeyer – Situation Suites

27 April – 16 June 2018

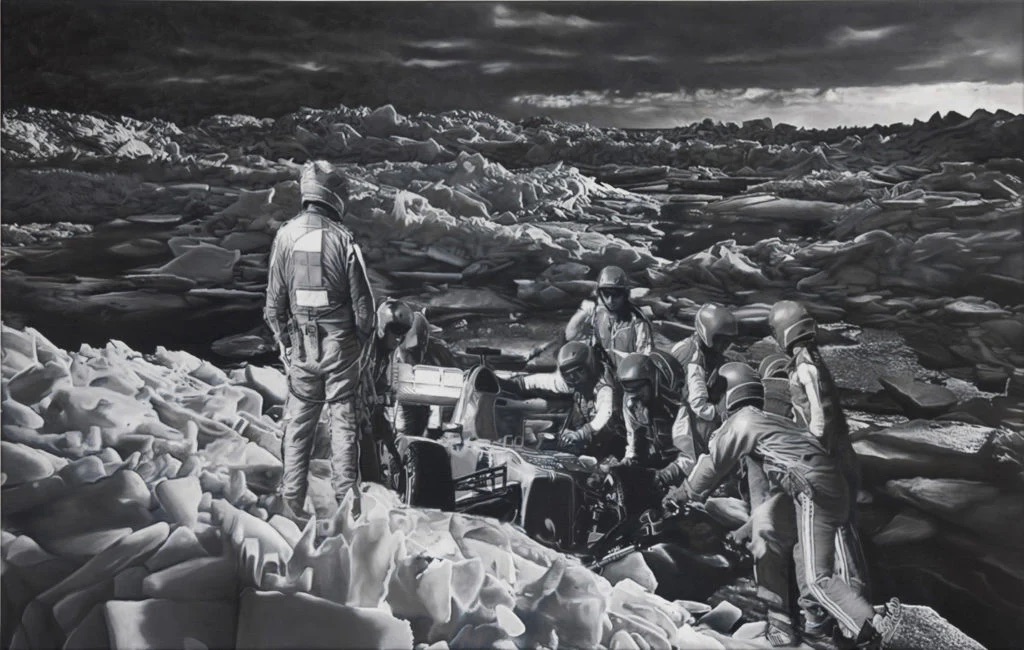

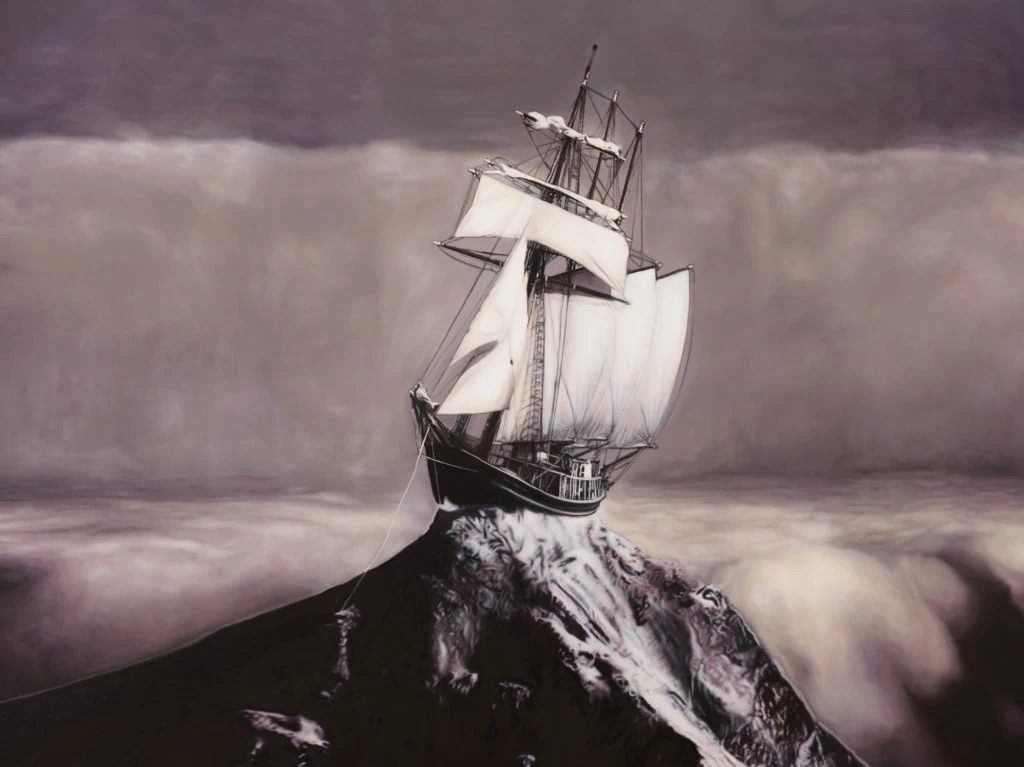

Clouds gather in a forest. A ship teeters on a mountain peak. Mechanics labor among glaciers. A bedroom looks in on itself. These are but a few of the nearly impossible scenarios one finds in Christoph Steinmeyer’s solo exhibition SITUATION SUITES at Galerie Michael Janssen.

Steinmeyer’s paintings challenge viewers and the very act of viewing, and they have prompted curator and critic Mark Gisbourne to position them in a category located between archaic and modern-day notions of amazement. In his essay, appropriately titled “From Wonderous Gaze To Marvellous Presence,” Gisbourne calls attention to the “distant, if not to say at times, somewhat puzzling realities” presented in SITUATION SUITES—a quality that gives them a surrealist tinge. But as he suggests with his citations of Aristotle, Descartes, Kant, and Borges, the works are as much in conversation with philosophy, literature, and music as they are with the history of art and the language of dreams.

These connections are explicit in Robert Browning Ouvertüre C. Ives (2018) and Clout, Save Me (2018). The former pays tribute to an early 20th-century overture by the American composer Charles Ives, which was, in turn, a tribute to the Victorian-era poet Robert Browning. The latter title references a ‘70s South African rock band, whose name (Clout) is the source of Steinmeyer’s pun. Both depict a cumulonimbus cloud amassed in the heart of a dark woods. At a glance they look identical except for differences in scale and tone. Despite their shared content, they are discreet artworks, which independently came into being during separate painterly actions. It is the artist’s mark—the evident hand—that diverts these works from being mere hyper/photorealistic duplicates. Significantly, they are known by different names linking them to different external influences—a conceptual gambit on the part of the artist, which deflects twinning and confounds the pictorial traditions to which they contribute.

Similar strategies are used elsewhere in the exhibition, albeit with a twist or flip. For example, the sailing ship in Das Dokument (2014) is reiterated in the smaller 22.03.2022 (2018). The vessel is still perched on a mountain peak and is still being (ironically) photographed by a mariner, but the images mirror each other, further layering the complexities already in play. This mutual inversion also occurs in the set Das Rennen (2015) and Das Rennen (Stop) (2018). Although their titles lead one to think the paintings might be depicting the same scene, the parenthetical “stop” truncates this thought. Halt those assumptions! It says. Not all pit stops are the same, even if they appear to be. Just as not all paintings of pit stops are the same, even if they tease the viewer into thinking they are.

Perhaps the most mind-bending element of the show is the namesake Situation Suite (2018). According to Gisbourne, the piece provides “a key to other paintings in the exhibition,” in that it opens “onto a world that appears eloquently plausible in the first instance, but when closely scrutinised reveals an unfolding conundrum of visual contradictions.” Here Steinmeyer has compounded his formal and conceptual antics into a single image: a mutely colored bedroom. From outside the frame, it seems possible the room is sandwiched between mirrors, yet not even a simple mise en abîme is spared the artist’s sabotage, for the reflections do not correlate to their context. And even if they did accurately repeat the interior design, they would do nothing to explain the liquesent downward pull occurring in the foreground—a proverbial slippery slope, which takes us into a mysterious world where causal relationships no longer abide by common expectation. Instead, the uncanny prevails.

Text: Patrick J. Reed

-

Michael Janssen Berlin is pleased to announce a solo exhibition by Christoph Steinmeyer entitled Bilder für Alle und Keinen. The exhibition comprises a series of paintings that bear the same name and that were part of the program of this year’s St. Moritz Masters in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

Macrocosm and Microcosm: The Body and the Void“The heightened realities of the paintings of Christoph Steinmeyer seem to avoid all the now historically belaboured terms that sought to imprison paint-based reproductive forms of realism in the late twentieth century. In the world of our current far reaching reproductive technologies the usefulness of defining images in terms of Photorealism, Super-Realism or more latterly post-Baudrillard ‘hyperrealism’, seems somehow irrelevant and intellectually out of date. Yet undoubtedly, and it is not denied, the painter Steinmeyer uses found resources derived from within photography, mass media and the internet, but nonetheless in the process of their subsequent translation they are removed from their original context and meaning. In fact rather than speak of the translated (which is simply to convert or move something from one context or meaning to another) they might be better described as having been transmuted—that is to say changed in their form or nature and subject—into a new understanding and visually redirected sense of reality. Hence they are less about realism, but rather inscapes of another heightened and vividly imagined personal reality.”

“….The paintings currently exhibited are part of a series of supercharged cosmological engagements with their human organic opposites. In these paintings such as Troy and Augenblick (Moment), the heart and the eye are superimposed upon the infinitude of a variable cosmological space. And while Steinmeyer often refers to them as an extension of his recent investigations into landscape, they are in fact better described as cosmological inscapes. The denial of an actual assertive realism—regardless of their meticulous execution—is predicated on the fact that as synthesised images, analogue source materials passed through a computer in filtered stages of integration in a manner of a digital collage, and after this reprocessed into their newly reconceived analogue form. In this way a sort of artist-generated and sublimated set of images emerges that serve as the basis for the imaginative paintings that are subsequently executed…..”

Mark Gisbourne

-

Christoph Steinmeyer – Hotel Déjàvu

25 January—28 February 2006

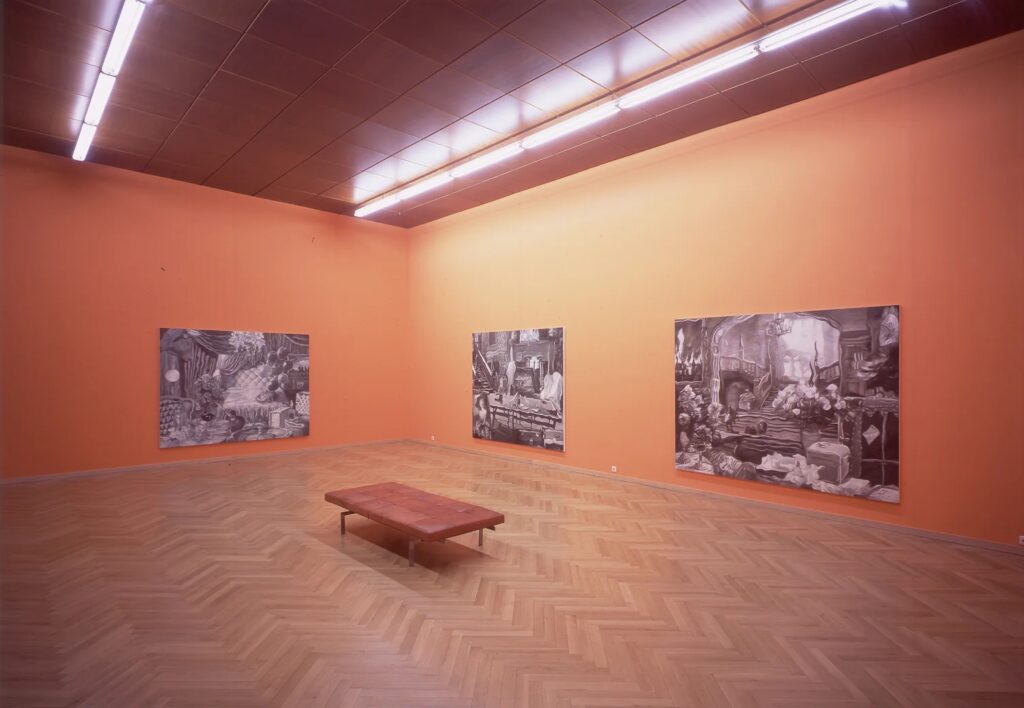

Galerie Michael Janssen, CologneThe Michael Janssen Gallery is pleased to announce the fourth solo exhibition by the Düsseldorf artist Christoph Steinmeyer.

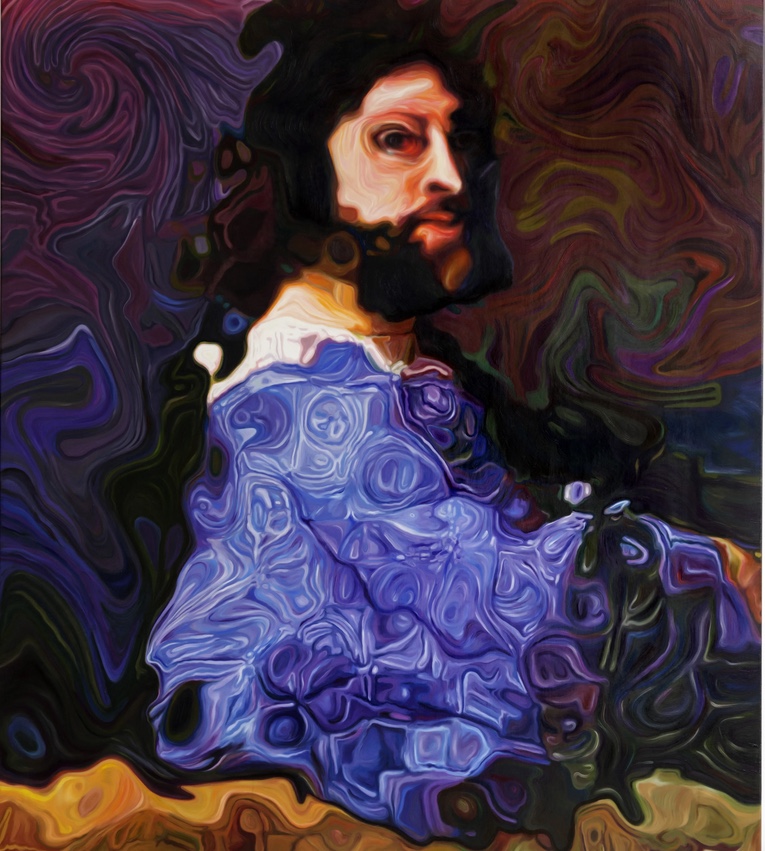

Christoph Steinmeyer (born 1967) belongs to a generation of artists that undercut both the authenticity of painting and the sources of their visual exploration. Since the mid-1990s, the Düsseldorf artist has been focussing on a kind of magical symbolism, and his subjects and artistic style resemble hybrids that have entered into a dangerous, deep-rooted liaison ever since. In 2002, he produced sumptuous interiors in which the synthetic surfaces braise Steinmeyer‘s painting as if using a Bunsen burner. A year later, the artist painted ghostly portraits whose strictly symmetrical form made them resemble modern Rorschach tests in a biotechnological age. It is no coincidence that the titles of these portraits – „Pandora“, „Medusa“ and „Sphinx“ – refer to the horror and hubris of gures like Pygmalion, whose role Christoph Steinmeyer skilfully applied to the medialised ideal types portrayed by the models he chose.

Even if the parallels with Pygmalion are clear, the main impression Christoph Steinmeyer creates is that he is revitalizing painting itself, rather than his subjects. This is due to the above mentioned way in which Steinmeyer deliberately refrains from lending greater significance to the plots or „storylines“ of his paintings than they actually contain. Although his subjects are substrata of a media image world (as propagated by the advertising, lifestyle and lm industries), Steinmeyer‘s images never refer to specific sources, always preferring an individual or collective perception of them instead. Consequently, Steinmeyer‘s pieces are not amalgamations that simply transform mass media images into paintings. They are more like hackneyed versions of medially transmitted patterns and models, which Steinmeyer transforms into new – equally imaginary – ideal types through his painting. Memory thereby combines with ideas to become a potential that no longer has anything to do with what one would call actual fact.

This method of playing with magical symbolism takes a new turn in the latest group of pieces by Christoph Steinmeyer. The sources for his paintings lie in lms, which are only referred to in the names of the title roles of their heroines: „Dolores“, „Gilda“ and „Rebecca“. The figures themselves never appear and even the lm sets that once formed the characters‘ stage are no longer directly recognizable. In fact, instead of transforming motifs from celluloid freeze frames, Christoph Steinmeyer compiles cliché elements from different scenes to enrich them – like a new plot – with additional symbolically laden props. In „Dolores“, a seemingly uniform historical atmosphere is pain- fully disrupted by the presence of a ping-pong table. Targeted image-within-image constellations repeatedly break the interior‘s space-time continuum. Despite stemming from lm sources, the guitar and roulette wheel used as props in „Gilda“ suddenly open up entirely new spaces for action. Candles and cellar vaults, masks and operating utensils merge in „Violet“ to form a deceptive still life. In „Rebecca“, the grandfather clock acts as a pointer, the initials on the suitcase are revealing and the countless used handkerchiefs leave behind a sense of sinister foreboding.Such adoption of film iconography is doubly irritating since it finds an extremely meaningful parallel in Steinmeyer‘s painting. He confronts the apparent authenticity of the black and white lm era with grisaille painting that only reveals ne, detailed chromatics after close inspection. The painting ows through the apparent beauty of such images in peristaltic waves – as if they were well known dream sequences on lm. And there are suitcases everywhere – from a large chest to a small cosmetics bag. One is tempted to open them and yet keep them shut, because the soul of such painting seems to emanate from them. It seems to brie y ll the canvas, before quickly retreating again. Like a lm. Like a dream. Finding such fantastic potential in painting is very rare. But it exists in the work of Christoph Steinmeyer. (Dr. Ralf Christofori)